Does anyone else have a favorite Rule of Civil Procedure? I do. It is Rule 1, particularly the last sentence which says that the Rules of Civil Procedure “should be construed, administered, and employed by the court and the parties to secure the just, speedy, and inexpensive determination of every action and proceeding.”

Does anyone else have a favorite Rule of Civil Procedure? I do. It is Rule 1, particularly the last sentence which says that the Rules of Civil Procedure “should be construed, administered, and employed by the court and the parties to secure the just, speedy, and inexpensive determination of every action and proceeding.”

I find myself turning to this rule more and more as I prepare papers for the court. No doubt that the Courts are dedicated to these three principles.

As to the principle of justice, the Nevada Supreme Court said in State ex rel. Sparks v. State Bank & Tr. Co., 37 Nev. 55, 66, 139 P. 505, 509 (1914):

[T]his tribunal under its supervisory power, is duty bound to safeguard the rights of all who seek justice at its portals.

When it comes to the principle of speed the Nevada Supreme Court said in the case of Dougan v. Gustaveson, 108 Nev. 517, 523, 835 P.2d 795, 799 (1992):

[T]hese provisions [of the Nevada Rules of Civil Procedure] recognize judicial commitment to the proposition that “justice delayed is justice denied.”

Finally, regarding the expense of the litigation process, in the case of Jones v. Lodge at Torrey Pines P’ship, 42 Cal. 4th 1158, 1167, 72 Cal. Rptr. 3d 624, 631, 177 P.3d 232, 238 (2008), the court recognized:

Litigation is expensive, for the innocent as well as the wrongdoer.

As any judge will tell you, the balance of these three principles is never easy.

That balance is well explained by Justice Stiglich in the case of Rodriguez v. Fiesta Palms, Ltd. Liab. Co., 134 Nev. 654, 654-55, 428 P.3d 255, 256 (2018) where she explained:

This appeal requires us to consider two fundamental interests of our justice system: the importance of deciding cases on the merits and the need to swiftly administer justice. Deciding cases on the merits sometimes requires courts to accommodate the needs of litigants—especially unrepresented litigants like the appellant in this case. Swiftly administering justice requires courts to enforce procedural requirements, even when the result is dismissal of a plaintiff’s case. We afford broad discretion to district courts to balance these interests within the context of an NRCP 60(b)(1) motion for relief. In this case, a district court denied a pro se plaintiffs NRCP 60(b) motion for relief that was filed five months and three weeks after the court dismissed his case because he did not comply with procedural requirements. That decision was not an abuse of discretion.

In the Rodriguez case, the principle of speed prevailed when the court refused to grant a Rule 60(b)(1) motion for relief from a dismissal after a prior trial on the merits, a remand for a new trial and then neither counsel nor the party appeared a pre-trial conference set for the second trial.

The case of Scrimer v. Eighth Judicial Dist. Court, 116 Nev. 507, 998 P.2d 1190 (2000) makes a good contrast. In Scrimer there are two cases consolidated into the one decision. Both cases involved NRCP 4(e) which requires service of a Complaint within 120 days of filing. The Nevada Supreme Court allowed both cases to proceed to discovery, causing the principle of speed to take the backseat to the principle of justice.

I encourage you to take another look at NRCP 1 and tell me after you study it if it doesn’t begin to grow on you.

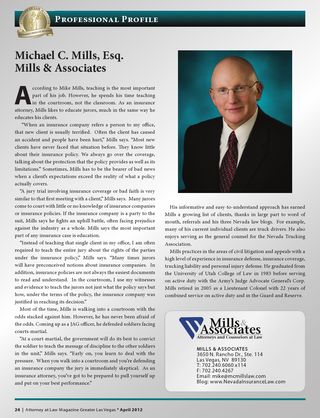

If you have questions about Nevada Coverage Law or Insurance Law in Nevada, please contact Mike Mills at 702.240.6060×114 or email him at mmills@blwmlawfirm.com.

Follow

Follow Email

Email