Auto insurance is not the only industry in which Nevada law provides protections to consumers. In a previous POST, we pointed out that the legislature precluded the enforcement of compulsory arbitration provisions in auto insurance policies.

Now the Nevada Supreme Court is getting into the act of refusing to enforce similar provisions in consumer sales contracts. In the recent case of Picardi v. Eighth Judicial Dist. Court, 127 Nev. Adv. Op. 9, 251 P.3d 723 (Nev. 2011), the Court found that a contract provision which waived the consumer’s rights to compel arbitration and thereby prevent the consumer from joining a class action suit was void as against Nevada public policy.

In Picardi, the Plaintiffs purchased an automobile, and subsequently sought to file a class action against Hyundai. Hyundai wanted binding arbitration and hoped to enforce the waiver of participation in a class action suit. The District Court upheld the arbitration clause which waived the consumer’s right to participate in a class action either in the courts or in arbitration and ordered the parties to arbitrate.

The dissatisfied Plaintiff filed a writ to the Nevada Supreme Court. However, the Court found itself between a rock and a hard place. In the past, the Court had said that it favored the idea of arbitration as a means to resolve disputes. However, it obviously saw the benefits that came to consumers from class action status. The Court reasoned that class actions were necessary where there may be numerous plaintiffs, similarly situated, but whose potential damages are too small to justify the expense of arbitration on a case by case basis.

The Court had hoped for an escape valve that would allow them to reconcile these competing interests. That escape valve would have been to require the parties to arbitrate but use the class action rules in the arbitration. However, the contract prohibited such an event. Because there was no escape valve, the Court found in favor of the consumer and struck down the arbitration clause altogether.

The lesson learned for the insurance industry is clear. Where a contract seeks to limit a consumer’s remedies, the language must be carefully crafted. See State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. v. Hinkel, 87 Nev. 478, 481, 488 P.2d 1151, 1153 (1971). Otherwise, there is a risk that Nevada Supreme Court will step in and strike down the offending provision.

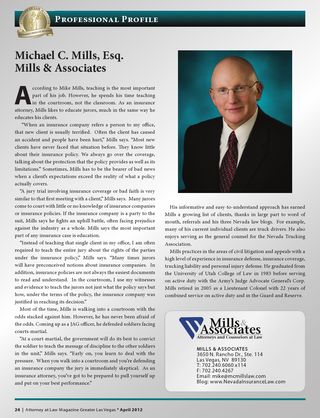

If you have questions about the interpretation of insurance policy provisions, please contact Mills & Associates.

Follow

Follow Email

Email